From December 1799 to May 1800, as ordinary American Protestants erected monuments to Washington’s corpse and collected his relics in the form of locks of hair and images, members of the House of Representatives dithered over plans to entomb his remains in the Capitol. They disagreed over the type of marble monument that would be erected over his corpse. Some wanted an equestrian statue of Washington. Others wanted a smaller monument. On May 8, a select committee on preserving Washington’s memory reported its progress. Members proposed erecting an equestrian statue of Washington in front of the Capitol. They also planned to move ahead with the construction of a smaller marble monument, under which Washington’s corpse would be deposited. They tentatively set aside $100,000 for the construction of the crypt, these monuments, and Washington’s reburial. When the resolutions passed to the whole committee of the House for a vote, Robert Goodloe Harper, a representative from South Carolina, proposed changes. He recommended erecting a mausoleum for the remains, instead of depositing them in the Capitol crypt and constructing the other two monuments. The changes to the proposal carried.

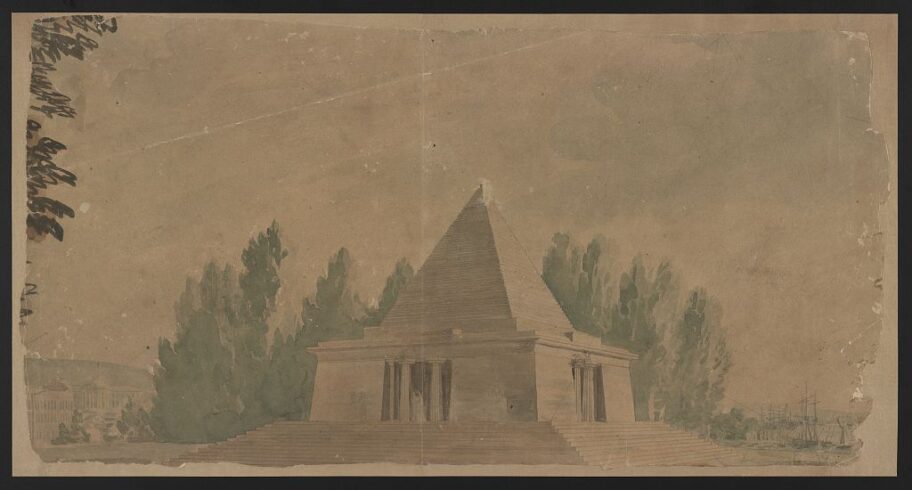

On May 9, the committee introduced a bill to build the mausoleum according to Benjamin Latrobe’s designs and estimates. The structure would be “a pyramid of one hundred feet at the bottom, with nineteen steps, having a chamber thirty feet square, made of granite, to be taken from the Potomac [River], with a marble sarcophagus in the centre, and four marble pillars on the outside.” Latrobe’s proposal included a watercolor of the mausoleum which showed the enormous pyramid structure supported by Doric columns and surrounded by a line of trees on the bank of the river. The mausoleum combined Egyptian and republican aesthetics to hold Washington’s corpse and materialize his immortality. According to the designs, Washington’s remains would not be at the center of the Capitol. They would be deposited in a sarcophagus in the center chamber of the mausoleum some distance from it. The design suggested that Washington’s remains were too important to be deposited in a building not specifically designed for them alone. Latrobe estimated that, with other appropriate ornaments, the mausoleum would cost $70,000. Disputes erupted in Congress over the cost, but most members did not want to reduce the monument’s size. The bill for erecting the mausoleum passed the select committee on May 10, by a vote of 54 to 19.

Over the next six months, members of the House squabbled over the exact design Washington’s monument should take. By Dec. 8, a few representatives still wanted to inter Washington’s remains in the Capitol and cover them with either a plain tablet or small monument. Most representatives, however, wanted to build the mausoleum for Washington’s corpse. Like Rev. Samuel Stanhope Smith, Roger Griswold, a representative from Connecticut, supported the construction of the mausoleum because he thought its enormity materialized Washington’s glory. “National sentiment,” he argued, “called for the erection of a structure correspondent in size to the character of the man to whom it was raised.” The mausoleum’s size mattered because it was supposed to act on viewers. Griswold explained that the mausoleum would “be pointed to our children; they will enter it with reverence, as the spot in which the ashes of this great man are deposited.” The mausoleum’s size would express the character of Washington’s remains and generate embodied sense experiences in children. Those who entered it were supposed to feel Washington’s presence. Likewise, another representative, Henry Lee of Virginia, explained:

We are deeply interested in holding them [Washington’s virtues and example] forth as illustrious models to our sons. Is there, then, I ask you, any other mode for perpetuating the memory of such transcendent virtues, so strong, so impressive, as that which we propose? The grandeur of the pile, we wish to raise, will impress a sublime awe on all who behold it. It will survive the present generation. It will receive the homage of our children’s children; and they will learn that the truest way to gain honor amidst a free people is to be useful, to be virtuous.

The mausoleum’s size, coupled with the remains, would impress children’s minds and bodies with the virtues of Washington. These congressmen, like Protestant ministers, recognized the importance of monuments and remains for providing supernatural, embodied sense experiences that would cultivate the virtuous and moral bodies of citizens. The debates dragged through December. On Dec. 23, the South Carolina representative John Rutledge suggested that time had been “idly wasted” since Washington’s death on these deliberations. He warned they had “delayed too long to do what ought to have been done at once.” Even so, debates over the type of monument continued that day. Finally, John Randolph of Virginia called the present “a tedious and useless debate.” He asked to whom they were pledged in this debate and for what. Randolph suggested that they were pledged “to the relicts of the deceased; to have them placed within these [the Capitol’s] walls” on the consent of Mrs. Washington. They should uphold their pledge to Washington, his relics, and Mrs. Washington. The debates were going nowhere fast.

The decision as to which type of monument Congress would construct for Washington’s relics eventually came to a vote on Jan. 1, 1801. The whole House voted and divided along party lines. Democratic-Republicans voted 34 to 3 against the bill, and Federalists voted 45 to 3 for it. The bill passed. Congress determined to move forward with plans to erect a giant mausoleum near the Capitol, in which to deposit Washington’s remains. Congress valued the preservation of Washington’s relics, and they showed their feelings with the exorbitant sum set aside for the project. Congress earmarked $200,000 for projected costs associated with a mausoleum designed by George Dance, eschewing the plans created by Latrobe. Dance was a British architect who helped found the Royal Academy in London. His design featured a pyramid 150 feet tall—far grander than Latrobe’s design.

But despite Congress’s vote to move ahead, the plans evaporated within the year. House and Senate members disagreed on a final version of the mausoleum. Washington’s corpse remained buried at Mount Vernon in the old family tomb until 1831, when the new tomb was completed.

Historians usually interpret these congressional debates as evidence of the divide between Federalists and Democratic-Republicans at the turn of the nineteenth century. Federalists lauded a mausoleum as evidence of social hierarchy, order in government, and leadership of heroic men. Democratic-Republicans favored a smaller monument and decried the mausoleum as an affront to republicanism, which should not foreground elite heroes above ordinary individuals. Kirk Savage has argued that the debates “represented the high-water mark of republican iconoclasm and a stunning rebuke to … hero worship.” Savage also suggested that “[t]he enlightened iconoclasm of Nicholas and Macon and other Republicans stemmed from the belief that an intelligent citizenry … no longer needed images to prop up its patriotism the way illiterate masses or decadent aristocrats had once needed imagery to spur their religious devotion.”

These debates certainly were about divisions between political parties and their ideologies. These debates are not, however, evidence of “republican iconoclasm.” Iconoclasm is defined by scholars of religion and material culture as “ritualized acts of violence … or the destruction of images.” Iconoclasm is an act or discourse that focuses on destroying or literally breaking, damaging, or defacing images, monuments, or statues. Iconoclasm is not just a “break with the past” over the ways images are created and employed. The debates between Federalists and Democratic-Republicans over Washington’s corpse and monument, then, were not about acts of iconoclasm in the ways some scholars have suggested.

The debates between Federalists and Democratic-Republicans centered on understanding the role and function of Washington’s relics and monuments to them in the new American republic. Federalists and Democratic-Republicans unanimously agreed that Washington’s remains should be deposited in the Capitol with a monument. All parties agreed that Washington’s corpse should be the foundation of the nation. Washington’s remains and a monument were essential, they said, for preserving his memory and perpetuating his glory to future generations of Americans. All parties agreed that, whatever form the monument took, it should exude the same moral and spiritual qualities as Washington’s remains. These debates, then, were about which type of monument would most appropriately reflect Washington’s republican presence, so that Americans would be suitably formed as republican citizens via embodied, supernatural sense experiences with his relics and the monument constructed over them.

Members of Congress understood that monuments for great leaders’ corpses were necessary for the formation of citizens, even if they could not agree on which type of monument to build for Washington’s corpse. Early national politicians were overwhelmingly Protestants who valued bodily relics and monuments as lively memory objects of the dead. They extended and adapted Protestant relic practices in their attempts to preserve Washington’s remains and construct a monument over them in the nation’s capital. Most members of Congress, like Smith, expected Washington’s remains and monument to generate his real presence, so it would mold Americans into virtuous and patriotic Protestant citizens.