Donald Trump’s re-election has sent many scrambling for historical comparisons. There is somehow comfort in the discovery (or at any rate the assertion) that there are precedents for even the most confusing and chaotic aspects of our uncertain present. Some will turn to the purging of dissent and anti-immigrant campaigns in the first and second red scares, or the authoritarian populism of Andrew Jackson’s Bank War. But the Reagan administration, which began with a self-inflicted economic crisis and the generational collapse of the American left, offers perhaps the most proximate analogy.

In his new book, The Last Supper: Art, Faith, Sex and Controversy in the 1980s (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2025), Paul Elie suggests, in a compellingly interwoven account of the evolution of religion, politics, and culture in this critical decade, that the age of Reagan may have never really ended. Tracking the histories of the Christian right’s rise to prominence in the Republican Party and in the broader culture, and the religiously-inflected responses of many artists and activists on the left to crises such as the AIDS epidemic and Reagan’s wars in Central America, Elie reveals the eighties as the moment when American religion became a force that divides, rather than unites, our country.

For much of the twentieth century, a staid, uncontroversial mainline Protestantism, along with the forms of Catholicism and Judaism that most closely resembled (and imitated) it, held the center of American public life. The explosions of alternative spirituality in the sixties and seventies, the concomitant rise of a more public Christian fundamentalism, and the decline of denominations like the Episcopal and Methodist churches, revealed religion not as a genteel middle-class consensus but as an arena for rival hyper-political visions for remaking the world.

It was in the eighties, Elie argues, that the polemical intensity of these competitions over the meaning of religion reached their present, enduringly desperate pitch. With verve, he retraces the major events of that era, from the end of the second wave of feminism to the end of the Cold War, while shedding new light on the patterns of American culture, through analyses of a staggering number of cultural artifacts, including, for example, a keen-eyed interpretation of the unlikely religious echoes in Michael Jackson’s music video for the single “Bad.”

Elie’s panoramic depiction of religion, politics, art, and popular culture is informative—and, given the often grim historical context and troubling portents for the present, surprisingly fun. Anyone interested in that era, or the antecedents of our own, will find many fascinating details and generative comparisons in this pleasurable and compelling exploration of a complex period that has been too often dismissed as a reactionary nadir of glib, glitz, and greed. The Last Supper finds nuance and pathos where others have seen only superficiality, offering, for example, a powerful interpretation of Andy Warhol’s queer religiosity and passionate engagement with Christian iconography amid the ravages of AIDS.

Elie reveals the eighties as the moment when American religion became a force that divides, rather than unites, our country.

Elie, an editor and magazine journalist and the author of books on subjects as varied as American Catholic writers and the uses of Bach over the centuries is able to tell a story, and indeed to keep many stories readably interlaced, but he often displays a blithe unawareness that his version of events is by no means self-evident and is in many cases tendentious or simply wrong. Consider two examples. One, midway through the book, is tangential to his overall argument, but shows a certain carelessness—or callousness—in interpretation that raises questions about his hermeneutic and ethical sensitivity. The other, only a few pages in, reveals a conceptual mess at the heart of his project.

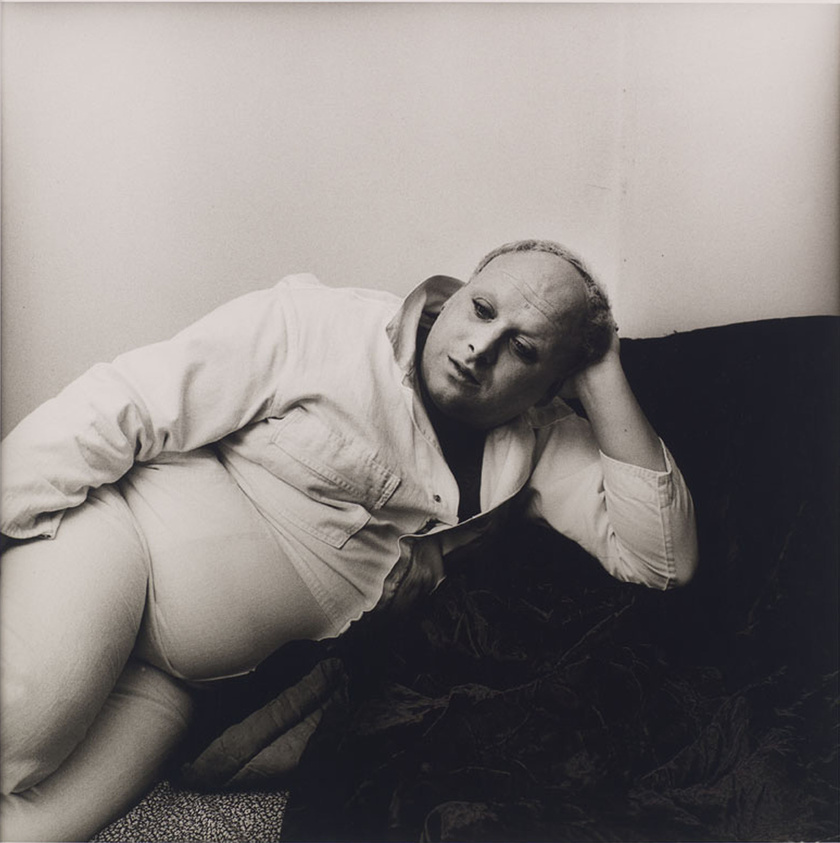

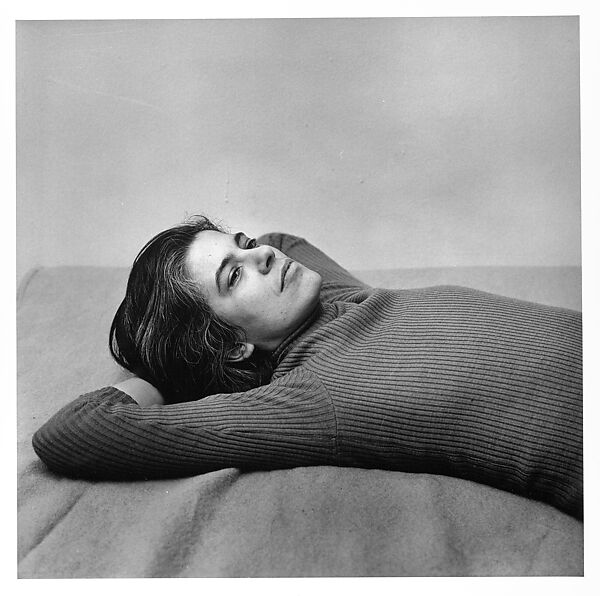

In the course of telling how a generation of artists, many but not all of them gay, addressed AIDS and challenged the hopelessly ineffective, often victim-blaming, reactions of the Roman Catholic church and Reagan administration, Elie devotes two paragraphs to the photographer Peter Hujar. Subject of a recent film (Peter Hujar’s Day) by Ira Sachs, Hujar was a central figure of the gay/queer downtown New York art world in the 1970s and 1980s, until his death from AIDS in 1987. Some of Hujar’s most famous works, even before the AIDS crisis began in the early 1980s, featured themes of mortality, such as photographs in catacombs or a death-bed portrait of Andy Warhol superstar Candy Darling. But Elie goes further than observing this commonplace (death must be up there with love as a perennial concern of nearly all artists). He interprets Hujar’s late-seventies portraits of queer celebrities, like the drag performer Divine and Susan Sontag, lying in bed as “a memento mori, suggesting the cryptic, death-haunted quality of the downtown scene—an effect that would seem premonitory” in light of AIDS.

Collected in the 1976 book Portraits in Life and Death, with a skull from the catacombs on its cover, these in-bed portraits might invite such an interpretation—if you look at them having already decided what you’ll see. But does Sontag, lying calm, smug, in self-conscious mental superiority over any potential viewer, really look, on second (or even first) glance, “death-haunted”? Perhaps this was one of the portraits in life. Hujar’s photos from this series, moreover, would have been more familiar to a gay audience through their appearance in a landmark 1977 issue of the magazine Christopher Street, the premier middle-brow magazine of arts, culture, and politics for gay men of that era. That issue featured Hujar’s smolderingly lively self-portrait (also in bed) on its cover, and, at the back of the magazine, paired Sontag with Divine in a deadpan diptych. Out of drag, plain-faced and pot-bellied, Divine seems, for once, not the loud, abrasive, hilarious character of the John Waters films that had made the drag performer famous, but more sensitive and pensive—and perhaps more genuinely thoughtful—than Sontag, whose pose of intellectual aplomb appears in comparison to be a mere put-on. Readers might have appreciated a multi-sided joke: Divine out of drag, looking like anyone’s uncle; Sontag bested on her own grounds of ostentatious intellectuality—and, what’s more, subtly outed, by her placement in such a series, decades before she publicly admitted her lesbianism.

Far from being simply morbid, or simply anything, Hujar’s photographs were complex (and beautiful) objects that took on new, contradictory meanings as they circulated among books, magazines, galleries, and private collections. They were decidedly not mere synecdoches of the pre-AIDS death drive of lower Manhattan’s queer artists. Describing New York’s downtown scene, whether then or now, is perhaps a sucker’s game, in any case, and Elie, who treats so many topics in his nearly five hundred page book, can well be forgiven for handling some of them simplistically. But a description of Christianity, and the eighties, in the first pages of his book shows that what appears to be inattention to detail may conceal a specific, partial, and in some ways polemical understanding of “religion.” He writes, in the prologue:

The Last Supper, in the Christian scheme of things, is both an end and a beginning: the end of Jesus’ time with his disciples, and the beginning of the religion established with the breaking of bread and the pouring out of wine.

The early eighties were both an end and beginning, at least where the place of religion in American life is concerned. The “long sixties” were ending, and the unsettled relationships among beliefs, institutions, and society broadly that defines the present moment was beginning, with a slow tectonic grind, to make itself felt.

These two paragraphs are short, readable and, on a first skim, clear. They communicate the main thesis of Elie’s book, reminding readers that the eighties were a time of religious change in the United States, and linking that reminder to what might seem to be a basic fact about Christianity, the religion that The Last Supper is really about. But there are also some grating and unfortunately representative stylistic problems. The metaphor “slow tectonic grind” shows sloppy haste or worrisome unconcern. The comparison Elie sets up between Christ’s inauguration of a new “religion” and the period examined in his book implies a radical, decisive, self-conscious split between a “before” and an “after,” not an almost imperceptibly gradual and steady transition, such as characterizes the movement of tectonic plates. And, then, one might ask if there is any moment, whether grindingly slow or dramatically innovative, that isn’t “both an end and a beginning,” it being almost as much of a cliché to observe that ends and beginnings come together as to note that crises are also opportunities.

The real problems with the passage, however, are conceptual. Elie makes a series of dubious substitutions and questionable implicit claims. The Christian religion, subject of the first paragraph, is elided into religion as such in the second. Throughout the book, Elie periodically reminds readers (and, as it were, himself) that Christianity is not the only religion in America, and that indeed the eighties were a time of growing religious diversity, but his focus is not only squarely on Christianity, but on a specific, contested, Catholic vision of Christianity. Many Christians, particularly Protestants, would not recognize their beliefs in Elie’s description of the Last Supper as a turning point—indeed the turning point—in the timeline of Jesus’ ministry. They would point, instead, to the Crucifixion as the pivotal moment when Christ redeemed the sins of the world, an act memorialized in the fellowship of the Lord’s Supper or symbolized in the sacrament of communion.

Christians, famously, do not agree about what this ritual is called or what they are doing by partaking in it. Nor do Christians agree that their religion was established at the Last Supper, rather than—to point to any number of other possibilities—the Great Commission, Jesus’ giving the Keys to the Kingdom to Peter, or Pentecost, when the Holy Spirit descended, many Christians believe, to start an ongoing relationship with believers individually and collectively that will endure until Jesus returns. It is by no means clear from the Bible when “the Church,” as a community of people believing in Jesus persisting in expectation of his second coming, was founded—or whether the Church, thus understood, is a religion. In my own evangelical upbringing, clergy and laity alike often insisted that Christianity is not a religion at all, but rather a relationship with God, founded on belief in his son, Jesus.

This may seem like a bunch of nit-picking over theological and terminological niceties (or not-so-niceties), but the disagreements that Elie breezes past are lengthy, still controversial chapters of ancient and modern Christian history. Elie, a Roman Catholic, writes as if a particular understanding of Christianity emerging from his own denominational perspective were synonymous with the “Christian scheme of things.” But in truth there is no “Christian scheme of things,” and indeed not even a Roman Catholic one. Christianity is an intense and interminable series of debates about a set of interrelated subjects, not least of which are the nature of religion and the meaning of the Last Supper.

In my own evangelical upbringing, clergy and laity alike often insisted that Christianity is not a religion at all, but rather a relationship with God, founded on belief in his son, Jesus.

It is crucial for Elie’s overall argument that he ignore this central, obvious fact of history and theology. The Last Supper’s analytical framework hangs on a distinction between what Elie takes to be straightforwardly orthodox expressions of religion, on the one hand, and “cryptic” religion, on the other. He is against the former, which appear throughout the narrative in such forms as various popes and future popes (Joseph Ratzinger) issuing what Elie, and any liberal, cannot but regard as reactionary and vicious injunctions against the use of condoms and the “intrinsically disordered” homosexual orientation, or lending support to authoritarian governments throughout the world. Critical of these, Elie is in favor of the “cryptic.” The Last Supper is a liberal, dissident Roman Catholic’s attempt, through a cultural and political history of a formative decade in American history, to critique his own faith and recover the resources for a revitalization of what he takes to be its best energies.

For this purpose, however, his terminology is ill-chosen. “Cryptic” religion does not mean what, literally, it ought to mean: concealed practice and/or belief. For Elie, “cryptic” is as expansive and vague as “queer” or “subversive” are in contemporary academic jargon; it refers to all forms of religion that express “something other than conventional belief.” It thus includes everything from the defiant action and writing of progressive clergy, liberation theologians, and other dissident Roman Catholics, to the use of Christian imagery by artists like Madonna and David Wojnarowicz. Elie thus glosses over the difference between people who claim to believe in Christ or be Christian, and non-believers who make use of Christian tropes. More problematically, as in his discussion of U2, he sometimes refuses to accept individuals’ explicit, direct statements that they are not religious, or not Christian, writing as if any engagement with Christian themes is evidence of some form of religiosity, albeit a “cryptic” one.

It does Christians no credit to refuse to take avowed non-Christians at their own word, attributing to them a faith they deny, and often oppose. Given that Christianity has been historically the predominant faith of the United States, and of many of its immigrants’ countries of origin, it is hardly surprising that everyone—from members of other faiths to atheists to lapsed Christians—sometimes express themselves by drawing on Christianity’s rich and contradictory set of symbols, texts, and practices. But to do so is not necessarily religious, let alone crypto-religious.

Elie’s overly inclusive notion of “cryptic” religion pairs with a reductive understanding of Christian orthodoxy, which is, as debates about the Last Supper or Christianity as a “religion” remind us, hardly uncontested. It is very difficult to say, in fact, what might be considered “conventional belief,” in opposition to the unconventional forms of spiritual expression analyzed (and usually celebrated) by Elie. His examples of convention in action tend to be the most conservative statements made by members of the Roman Catholic and evangelical clergy, at the height of their alliance with the Republican Party in the era of Reagan.

But, of course, that alliance was itself a historical novelty, a radical departure from the mutual theological hostility that had divided Catholics and Protestants in the United States. “Conservative” religious leaders were innovators, not mere followers of convention. And many Christians with ostensibly conservative politics, then and now, not only innovate in order to pursue their goals, but also make unexpected, complex (in fact “cryptic”!) accommodations with the culture around them. Any attempt to separate “conventional” from “cryptic” sorts of religion is bound to end in paradoxes—which may be nevertheless, as most of Elie’s stories are, fascinating, provocative, and timely.