In the 1960s, as large interfaith coalitions marched on Washington for civil rights and as the Vatican issued Nostra Aetate, rejecting the idea of Jewish guilt for Jesus’ death and encouraging Jewish-Christian dialogue, one towering figure of American Jewry sought not dialogue but distance.

Joseph B. Soloveitchik (1903–1993), known as “the Rav,” argued that Jews should avoid deep theological discussions with Christians, limiting dialogue to practical matters like public policy. His stance, articulated in his seminal 1964 essay “Confrontation,” sparked debate, especially as interfaith dialogue continuously gained traction post–Vatican II, a 1965 council that liberalized the church. Yet Soloveitchik’s own engagement with Christian thinkers and his nuanced private views muddied the waters, inspiring his disciples—especially Irving (“Yitz”) Greenberg, David Hartman, and Jonathan Sacks—to challenge his public position and embrace theological dialogue. What can we learn from Soloveitchik’s caution, the bold dissent of his students, and the enduring continuity between them—especially as we live through this current period of divisiveness among different faith groups? By situating the discussion between Soloveitchik and his students within the evolving landscape of American Orthodox Judaism—a community navigating modernity, assimilation, and institutional growth amid broader political, social, and economic shifts in post-war America—we can see just how much this period of disagreement within Orthodox Judaism can teach us today.

Jewish-Christian relations have historically been fraught, marked by centuries of mistrust and violence. The Holocaust, however, was a turning point, exposing the catastrophic consequences of antisemitism and prompting a reevaluation of interfaith dynamics. Scholars like Jules Isaac, a French historian who lost his family in Auschwitz, saw an opportunity for reconciliation. On June 13, 1960, Isaac met Pope John XXIII, urging the Catholic Church to confront its role in fostering antisemitism. This brief but momentous meeting, lasting roughly twenty to thirty minutes, put the Church’s relationship with Judaism on the agenda of the Second Vatican Council, influencing the drafters of Nostra Aetate (1965). This Vatican II document rejected the notion of collective Jewish guilt for Jesus’s death, marking a seismic shift in Catholic-Jewish relations.

Abraham Joshua Heschel, a Polish-born rabbi, also contributed to these developments. In 1964, he pressed Pope Paul VI to eliminate the deicide charge entirely from Catholic doctrine and succeeded in compelling the pope—in the final draft of Nostra Aetate—to do away with the imperative that had urged Catholics to seek to convert Jews. The final version of Nostra Aetate removed the deicide charge as well (likely due, at least in part, to Heschel’s influence).

But these efforts, while groundbreaking, unsettled some Orthodox Jews, who viewed interfaith engagement as a threat to Jewish identity. The Orthodox Young Israel movement, for instance, criticized Heschel’s dialogue with the pope as a “flagrant violation” of communal consensus, deeming it “degrading” for Jewish leaders to “beg” before Christian authorities.

American Orthodox Judaism in the 1960s was itself at a crossroads, grappling with its place in a rapidly modernizing society. The post-war economic boom, along with suburbanization, brought unprecedented opportunities for Jews, including Orthodox communities, to integrate into American life. This period saw significant growth in Orthodox institutions, including New York’s Yeshiva University (where Soloveitchik taught), which became a hub for training Modern Orthodox rabbis equipped to navigate both Torah and secular culture. Politically, the civil rights movement influenced less orthodox Jewish leaders to engage in broader social-justice efforts, often alongside Christian groups, fostering a climate in which interfaith cooperation on civic issues became more acceptable. However, this integration raised fears of assimilation, particularly among Orthodox Jews, who sought to preserve their distinct identity.

These efforts, while groundbreaking, unsettled some Orthodox Jews, who viewed interfaith engagement as a threat to Jewish identity.

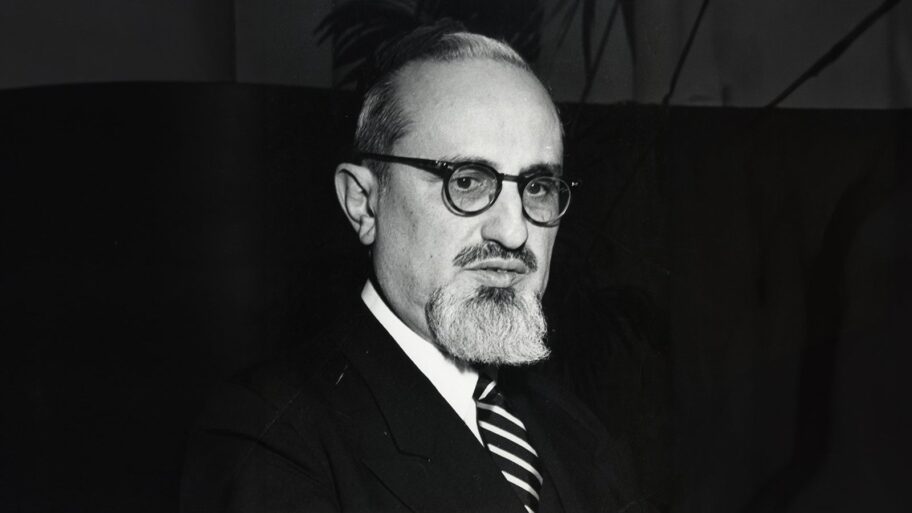

Enter Soloveitchik, the preeminent voice of Modern Orthodoxy. Born in Belarus in 1903, he earned a Ph.D. in philosophy in Germany before immigrating to America in 1932. At Yeshiva University, he trained generations of rabbis and authored influential works like The Lonely Man of Faith (1965) and Halakhic Man (1983). His authority was near-absolute, and opposing him risked alienation within the Modern Orthodox community.

In “Confrontation,” delivered in 1964 at the Rabbinical Council of America’s Mid-Winter Conference and published in the journal Tradition, Soloveitchik argued that Jews and Christians could collaborate on social issues but must avoid theological dialogue. He posited that each faith’s essence—its “private, sacred core”—was incommensurate, expressed through a “singular normative gesture” that could not be translated or discussed across traditions. Theological exchange, he warned, risked standardizing or universalizing the irreducibly distinct experiences of Judaism and Christianity, leading to futility and potential discord.

Yet Soloveitchik’s own actions complicated his stance. He engaged deeply with Christian theologians like Søren Kierkegaard, Karl Barth, Rudolph Otto, and Paul Tillich, weaving their ideas into his philosophy. In 1961, he presented the essay that would later be published as The Lonely Man of Faith—a work steeped in Jewish theology—to a Catholic seminary in Brighton, Mass. This apparent contradiction suggested that Soloveitchik was not wholly opposed to interfaith exchange but sought to control its scope, perhaps to protect a community wary of assimilation.

Theological exchange, Soloveitchik warned, risked standardizing or universalizing the irreducibly distinct experiences of Judaism and Christianity, leading to futility and potential discord.

This caution resonated with the broader Orthodox struggle to maintain halakhic fidelity, fidelity to religious law, while participating in America’s pluralistic society. The 1960s saw Orthodox Jews increasingly visible in public life. Rabbis like Soloveitchik were consulted on issues like civil rights and urban policy. Yet the rise of countercultural movements and liberalizing trends in American religion, including within Reform and Conservative Judaism, heightened Orthodox concerns about maintaining boundaries, making Soloveitchik’s restrictions a strategic response to a community under pressure. His 1967 addendum to “Confrontation” (published in the volume A Treasury of Tradition, edited by Norman Lamm and Walter Wurzburger) clarified his position, explicitly opposing “public debate, dialogue or symposium concerning the doctrinal, dogmatic or ritual aspects of our faith” while endorsing discussions on “universal religious problems” and “humanitarian and cultural endeavors.”

But Soloveitchik’s caution did not go unchallenged. His disciples—men like Irving Greenberg, David Hartman, and Jonathan Sacks—belonged to the “second generation” of American Orthodox theologians. Unlike Soloveitchik’s immigrant generation, which focused on preserving tradition amid modernity, these thinkers embraced the openness of their cultural context in the United States (in the case of Hartman and Greenberg) and in the United Kingdom (in the case of Sacks). Shaped by the post-Holocaust imperative to prevent religious violence, and by the opportunities opened by Nostra Aetate, they saw theological dialogue not as a threat but as a tool for mutual understanding and reconciliation. Their willingness to engage Christians theologically mirrored broader shifts in American Orthodoxy, as younger rabbis and laypeople, educated in Modern Orthodox institutions (which prioritized traditional Torah practice and study, but also embraced scientific and humanistic study), felt more secure in their Jewish identity. The establishment of organizations like the Orthodox Union’s National Conference of Synagogue Youth (NCSY) in the 1950s and 1960s fostered a confident, Americanized Orthodoxy that was less fearful of external influences. Socially, the decline of overt antisemitism in post-war America and the increasing acceptance of Jews in professional and academic spheres emboldened these thinkers to explore interfaith dialogue as a means of asserting Jewish presence in a pluralistic society.

Irving “Yitz” Greenberg (b. 1933), a rabbi and scholar, was a devoted student of Soloveitchik, having come into his orbit in Boston and becoming a disciple of his when Greenberg became a professor at Yeshiva University. Yet Greenberg diverged sharply from his teacher on interfaith dialogue. In 1967, Greenberg participated in a Jewish-Christian conference in Boston, engaging directly in theological discussions. He believed such dialogue could reduce hatred and foster cooperation, especially as Christians sought repentance post-Holocaust. Greenberg’s commitment to interfaith engagement became a cornerstone of his work, culminating in his 2015 essay, “To Do the Will of Our Father in Heaven: Toward a Partnership Between Jews and Christians,” published by the Center for Jewish-Christian Understanding and Cooperation (CJCUC) and co-signed by nearly thirty Orthodox rabbis, including prominent figures like Shlomo Riskin and Eugene Korn. Korn argued that Soloveitchik’s ban on theological dialogue was no longer applicable, noting, “Jews have real enemies today, but Christians are no longer among them.”

Greenberg’s break with Soloveitchik was rooted in both philosophical and personal convictions. Philosophically, he drew inspiration from Franz Rosenzweig, whose positive view of Christianity as a complementary covenantal path contrasted with Soloveitchik’s neo-Kantian skepticism, influenced by Hermann Cohen’s critical stance toward Christianity. Elsewhere I have argued that these philosophical differences—Cohen’s influence on Soloveitchik and Rosenzweig’s on Greenberg—partly explain their divergent approaches. Rosenzweig’s 1921 book The Star of Redemption posits Judaism and Christianity as twin covenantal paths, each essential to God’s redemptive plan, a framework Greenberg adopted to advocate for a Jewish-Christian partnership. Cohen’s ethical monotheism, meanwhile, informed Soloveitchik’s emphasis on the radical individuality of religious experience, aligning with his view of theological incommensurability.

Greenberg also confronted Soloveitchik directly, as recounted in his 2004 book For the Sake of Heaven and Earth. In a private conversation, Greenberg challenged the distinction between social and theological dialogue, citing Soloveitchik’s teaching that halakhah, Jewish law, governs all life sseamlessly. Soloveitchik conceded, “Greenberg, you are right.” He admitted there were no halakhic barriers to theological dialogue and did not object to Greenberg’s plans. This exchange revealed Soloveitchik’s public stance as a strategic maneuver to shield a cautious community, not an absolute prohibition. Greenberg interpreted “Confrontation” as “Marrano writing”—a text with a surface message masking a deeper openness to dialogue. Soloveitchik’s private acquiescence emboldened Greenberg to pursue theological exchange, framing it as an extension of his mentor’s halakhic worldview. In a written message to me, Greenberg elaborated: “The Rav’s emphasis that Judaism was a world religion … did influence me a lot,” suggesting that Soloveitchik’s global vision of Judaism as a peer to Christianity indirectly shaped Greenberg’s dialogical approach.

Greenberg’s dissent was not merely a rejection of Soloveitchik’s caution but a reinterpretation of his teachings. By arguing that interfaith dialogue could prevent future atrocities, Greenberg aligned with Soloveitchik’s broader concern for Jewish survival, extending it into a new context. His participation in interfaith conferences and his advocacy for theological partnership reflected a belief that Christians’ post-Holocaust teshuvah, repentance, demanded a Jewish response, a view shared by other second-generation thinkers like Emanuel Rackman, who noted the openness of this cohort to dialogue with non-Jewish intellectuals.

Greenberg’s approach also reflected the growing assertiveness of American Orthodoxy, which, by the 1970s, was bolstered by institutional developments like the expansion of kosher-food certification and the founding of new yeshivas. Economically, the prosperity of American Jews enabled the creation of interfaith organizations, such as the National Jewish Center for Learning and Leadership (CLAL), co-founded by Greenberg, which promoted dialogue as a means of strengthening Jewish identity in a pluralistic society. Politically, the rise of the American Jewish lobby—particularly after Israel’s 1967 Six-Day War—gave Orthodox Jews a sense of global influence, encouraging figures like Greenberg to engage confidently with other faiths.

By arguing that interfaith dialogue could prevent future atrocities, Greenberg aligned with Soloveitchik’s broader concern for Jewish survival, extending it into a new context.

David Hartman (1931–2013), founder of the Shalom Hartman Institute, was a student of Soloveitchik’s at Yeshiva University. Yet, even after receiving rabbinic ordination from Soloveitchik, Hartman also rejected his restrictions, inspired by Soloveitchik’s own engagement with Christian thinkers. Soloveitchik introduced Hartman to Kierkegaard and Otto to deepen his understanding of prayer, a pedagogy that Hartman found transformative. In Halakhic Man, Soloveitchik cites Christian theologians approvingly, juxtaposing Jewish and Christian sources with intellectual vigor—putting Maimonides in dialogue with Thomas Aquinas and Solomon ibn Gabirol with Duns Scotus. Hartman wrote, “Suddenly, like a cool, refreshing breeze, a new religious phenomenology became alive to me.” This cross-cultural approach convinced Hartman that Soloveitchik’s barriers were not absolute but a high bar for Jews confident in their faith’s uniqueness.

Hartman read “Confrontation” as permitting theological dialogue for those who could bear the “burden of solitude”—the awareness of Judaism’s incommensurability with other faiths, as articulated in The Lonely Man of Faith. He argued that Soloveitchik trusted Jews who could engage in dialogue while preserving their covenantal loneliness. Hartman’s interfaith work through the Shalom Hartman Institute emphasized mutual learning while maintaining Jewish distinctiveness, aligning with Soloveitchik’s model of engaging Christian thought. For instance, Soloveitchik’s use of Otto’s concept of the “numinous” in his essay on prayer and his borrowing from Tillich in constructing “Majestic Man” in The Lonely Man of Faith demonstrated a willingness to draw on Christian categories to enrich Jewish theology—a practice Hartman emulated in his own engagement in dialogue.

Hartman’s efforts also coincided with a period of Orthodox institutional growth in America and Israel, where the Shalom Hartman Institute (founded in 1976) became a center for pluralistic Jewish thought. Socially, the 1970s and 1980s saw American Orthodox Jews increasingly engaging with feminist and egalitarian movements, which, while controversial, opened discussions about modernity and external influences. Hartman’s institute, located in Jerusalem but influential in America, reflected this trend by promoting interfaith dialogue as a way to articulate Jewish values in a global context, supported by the economic stability of American Jewish philanthropy.

Hartman’s conviction that dialogue was permissible was further reinforced by Soloveitchik’s presentation of The Lonely Man of Faith to a Catholic audience, the one in Massachusetts, an act that seemed to contradict his public stance. Hartman saw this as evidence that Soloveitchik’s opposition was not rooted in halakhah but in communal caution. Hartman’s institute became a hub for interfaith engagement, fostering discussions that respected the “untranslatability of the complete faith experience” while promoting mutual understanding, thus extending Soloveitchik’s intellectual openness into practical dialogue.

Soloveitchik’s use of Otto’s concept of the “numinous” in his essay on prayer and his borrowing from Tillich in constructing “Majestic Man” in The Lonely Man of Faith demonstrated a willingness to draw on Christian categories to enrich Jewish theology—a practice Hartman emulated in his own engagement in dialogue.

Jonathan Sacks (1948–2020), Great Britain’s chief rabbi from 1991 to 2013, took Soloveitchik’s legacy global, advocating passionately for interfaith dialogue. In Faith in the Future (1995), Sacks—who was never a formal student of Soloveitchik’s but who was profoundly influenced by his thought—called Jewish-Christian dialogue “one of the great religious achievements of the past half-century.” Thinking of the ethno-rigious conflicts in the former Yugoslavia, he argued that religion, having fueled violence, must contribute to healing. “If religion is part of the problem,” Sacks wrote, “then religion must be part of the solution.” He saw interfaith dialogue as an “interfaith imperative,” essential to preventing future religiously motivated catastrophes.

Sacks’s support for dialogue stemmed from his theological pluralism and personal experiences. He believed all humans, created in God’s image, deserve respect, and interfaith dialogue fosters this by honoring others’ faiths while learning from them, such as the Christian tradition of pastoral ministry, which Jews have incorporated. His childhood at a Christian school in London taught him the value of interfaith encounters, reinforcing his commitment to tolerance. Sacks’s pluralism allowed him to celebrate Christianity as a valid covenantal path, as seen in his gratitude for helping a Christian recover her faith in Christ: “I thanked God for the privilege of bringing his word to another person.” Yet, he maintained Soloveitchik’s emphasis on the distinctiveness of each faith, rejecting convergence as a goal of dialogue.

Sacks’s experiences with Christian leaders, such as Cardinal George Basil Hume and the Archbishop of Canterbury, were “unexpected delights” that shaped his advocacy. His participation in a 1994 Jewish-Catholic conclave in London and his lecture at the Inter-Faith Conference on Democracy at Westminster Abbey in 1993 underscored his commitment. The Vatican’s 1993 recognition of Israel further convinced Sacks of the need for reconciliation, as he wrote, “Ancient hostilities do not die overnight. But neither are we condemned to replay them forever.” His theological anthropology—rooted in the biblical command to love the stranger (Lev. 19:18)—drove his belief that dialogue could strengthen faith across traditions without diluting Jewish identity.

Sacks’s global perspective was shaped by the internationalization of Modern Orthodoxy, as institutions like Yeshiva University trained rabbis who served worldwide, including in Britain. Politically, the 1990s saw rising multiculturalism in Western societies, which encouraged religious leaders like Sacks to promote dialogue as a model for coexistence. Economically, the globalization of Jewish philanthropy supported interfaith initiatives, enabling Sacks to build bridges with Christian communities while maintaining Orthodox authenticity.

The rift between Soloveitchik and his disciples is striking, but the continuity is more profound. Soloveitchik’s permission for any Jewish-Christian dialogue—however limited—was revolutionary in an Orthodox world in which figures like Yeshayahu Leibowitz opposed all interfaith engagement. By allowing dialogue on civic and cultural issues, Soloveitchik opened a door that Greenberg, Hartman, and Sacks widened to include theology. Soloveitchik’s own engagement with Christian thinkers provided a model for his students, who took his intellectual openness to its logical conclusion: dialogue with living Christians.

Greenberg’s confrontation with Soloveitchik illustrates this continuity. By invoking Soloveitchik’s teaching of halakhah’s seamlessness, Greenberg framed his interfaith work as an extension of his mentor’s philosophy. Soloveitchik’s private concession—that no Jewish legal barriers existed—further legitimized Greenberg’s path. Hartman, inspired by Soloveitchik’s use of Christian sources, saw dialogue as a natural outgrowth of his teacher’s intellectual courage. Sacks, while bolder in his global advocacy, echoed Soloveitchik’s emphasis on faith’s distinctiveness, ensuring dialogue respected Judaism’s uniqueness.

These differing views of interfaith exchange reflect differing philosophical inclinations and commitments. Soloveitchik’s neo-Kantian framework, influenced by Hermann Cohen, emphasized the radical individuality of religious experience, aligning with his view of theological incommensurability. Cohen’s critical stance toward Christianity, rooted in his ethical monotheism, resonated with Soloveitchik’s caution. Conversely, Greenberg’s embrace of dialogue drew on Rosenzweig’s view of Judaism and Christianity as complementary covenantal paths, each essential to God’s plan. Hartman’s approach bridged these perspectives, using Soloveitchik’s intellectual openness to justify dialogue while preserving Jewish distinctiveness. And Sacks’s pluralism, while distinct, aligned with Rosenzweig’s vision of multiple valid paths to God.

These various paths remain with us today—Soloveitchik’s caution, as well as the differing philosophies of his students. Soloveitchik’s reservations reflected the 1960s’ anxieties about assimilation, but his openness to limited dialogue laid the groundwork for his disciples’ boldness. Greenberg, Hartman, and Sacks transformed Jewish-Christian relations, proving that dialogue could strengthen Jewish identity while cultivating mutual respect. Their work unfolded against a backdrop of American Orthodoxy’s growing confidence, driven by institutional expansion, economic prosperity, and political influence. The rise of Modern Orthodox advocacy groups, such as the Orthodox Caucus in the 1990s, reflected a community increasingly willing to engage with broader society while maintaining its distinctiveness. Socially, the integration of Orthodox Jews into American professions and academia reduced the insularity that had shaped Soloveitchik’s era, enabling his disciples to pursue dialogue without fear of losing Jewish identity. Their efforts also reflected global trends, as the post–Cold War era emphasized interreligious cooperation to address conflicts like those in the Balkans, which Sacks explicitly referenced.

The legacy of Joseph B. Soloveitchik and his disciples Irving Greenberg, David Hartman, and Jonathan Sacks remains profoundly relevant to contemporary Jewish-Christian interfaith efforts, particularly in addressing the persistent challenge of antisemitism and fostering mutual understanding in an increasingly polarized world. Soloveitchik’s cautious approach to theological dialogue, as outlined in “Confrontation,” was rooted in a post-Holocaust concern for preserving Jewish identity amidst historical trauma and assimilation pressures. His disciples, however, embraced theological engagement, seeing it as a means to combat prejudice and build bridges, a stance that resonates today as antisemitism surges globally—evidenced by a 2024 Anti-Defamation League report documenting a 140-percent increase in antisemitic incidents in the U.S. since 2020. Their advocacy for dialogue, grounded in Soloveitchik’s intellectual openness yet bold in its expansion, offers a model for navigating these tensions, encouraging Jews to engage confidently with Christians while maintaining covenantal distinctiveness.

In 2025, as religious and ethnic divisions fuel global conflicts, such as those in the Middle East and Eastern Europe, the approach of Soloveitchik’s disciples provides a framework for interfaith cooperation that counters misunderstanding and hatred. Greenberg’s emphasis on partnership, Hartman’s focus on mutual learning, and Sacks’s theological pluralism—each building on Soloveitchik’s legacy—equip Jewish communities to address antisemitism not through isolation but through dialogue that fosters empathy and shared ethical commitments. This is particularly vital in countering online misinformation and extremist rhetoric—which often amplify antisemitic tropes—by promoting informed, respectful exchanges that affirm Jewish identity while engaging Christian allies in the fight against bigotry. Their work underscores that interfaith dialogue, when rooted in mutual respect and theological integrity, remains a powerful tool for building resilient, inclusive societies today.