When John W. Radcliff II, a longtime youth pastor at Southern Baptist churches in West Virginia, was charged recently with nearly two hundred counts of sexual abuse crimes, involving children and family members, the jokes could almost write themselves—not just about stereotypes of Appalachia, but about youth pastors. Because, to judge from the news, it does seem that this is a uniquely troubled, or troubling, guild. In the past ten years, youth pastors, or pastors leading youth groups, have been arrested for sexual crimes in, among other places, Oregon, Virginia, Arkansas, Texas, and, just last week, Minnesota.

Someone from outside the evangelical subculture might be tempted to ask, “What’s going on with youth pastors?”

It’s not a misguided question. In basements and hangout rooms in churches across the country, ice-breaker games and pizza nights cultivate a specific subculture of American evangelical youth groups. Teenagers close their eyes and raise their hands while singing catchy praise songs, and they are encouraged to recruit their peers into the spiritual fold. For decades, these evangelical groups have blended clean fun with edgy spiritual messaging to keep kids hooked on Jesus. Close relationships formed with peers, often under the guidance of special youth ministers, can be transformative but also an opportunity for abuse.

Somehow, I escaped youth-group culture. Raised in an evangelical church in the 1990s and early 2000s, our church was too conservative for edgier youth groups, and leaders believed parents should ultimately lead the children’s spiritual direction throughout their teenage years. We were expected to join Bible studies and theology classes as any of the grown-ups would, using a concordance to check the Hebrew and the Greek and reading texts by Protestant reformers John Calvin or Martin Luther.

Someone from outside the evangelical subculture in which these crimes took place might be tempted to ask, “What’s going on with youth pastors?”

But I heard stories from evangelical peers. Youth groups were a breeding ground for the 1990s purity culture movement, which encouraged evangelical teens to “guard their hearts,” maintain virginity for a future spouse, and pursue courtship instead of dating (the message of the 1997 book I Kissed Dating Goodbye, then a must-read in certain circles). This is also where evangelical youth are often taught conservative moral values around abortion, LGBT issues, contraception, and pornography.

In some ways, I am grateful I skipped the youth-group world. Youth groups are sometimes criticized as “spiritual daycare” because they can silo and isolate teens from the larger congregation, making it harder for them to eventually integrate into grown-up ministry. “It was an alternate social life for kids that could be supervised,” David Zahl, the founder of Mockingbird Ministries who has himself led youth ministry, told me. “The boogeyman of sex and alcohol could be avoided.”

Evangelicals who grew up in youth groups are now either deeply nostalgic about their youth group or else describe it as a scarring experience, Zahl said. But the youth minister, someone who served as a mix between an adult and an older sibling, makes all the difference. “Youth ministers will now say, part of what they do is show kids how to hang out without phones,” Zahl said. “They’ll bring out a guitar and experience campfire singing.” Such figures can be transformative in the lives of today’s teens.

For many churches and parents, the goal of youth groups is simple: retention.

Other traditional religious groups have their own versions of educating their youth, but they look different from such groups in the Protestant world. Jewish youth attend Hebrew school before their bar or bat mitzvah, Catholic youth can attend Rite of Christian Initiation (RCIA) classes before confirmation, and Latter-day Saint (Mormon) teens are encouraged to attend “seminary,” a daily class that often meets in the morning before school.

For many churches and parents, the goal of youth groups is simple: retention. Religious institutions are bleeding congregants, and youth groups can be a way to make the faith more attractive and sticky. Youth groups are one of the key reasons evangelical churches haven’t bled as many congregants as, say, the mainline Protestant tradition, according to Duke University sociologist Mark Chaves.

“Evangelical churches invest more than mainline churches in youth ministries, and it is difficult to avoid the conclusion that this investment difference reflects a difference in the priority placed on keeping young people in the church,” Chaves wrote for the website Faith & Leadership.

Many evangelical churches employ special youth ministers, someone in their twenties, to help guide teens spiritually and maybe introduce Christian apologetics to defend the Christian faith. Through youth groups, many teens attend Christian overnight camps and overseas mission trips, often designed to intensify their faith experience and get teens to share the faith with others.

Before the 1970s, evangelical youth ministry didn’t really take place inside churches, according to Christianity Today. Organizations like Youth for Christ (YFC) informally began in 1940, hiring the evangelist Billy Graham as its first employee. Churches saw the draw and adopted their own versions, often focused on community-building activities like trust falls and sometimes promoting Christian books such as the end-times Left Behind series. Many evangelicals who grew up in that culture eventually “deconstructed” out of their faith entirely. While youth groups have largely flown under the mainstream media’s radar, there was a brief moment in the literary spotlight, when Jonathan Franzen wrote about a mainline Protestant youth group in the 1970s in his 2021 novel, Crossroads.

Before the 1970s, evangelical youth ministry didn’t really take place inside churches.

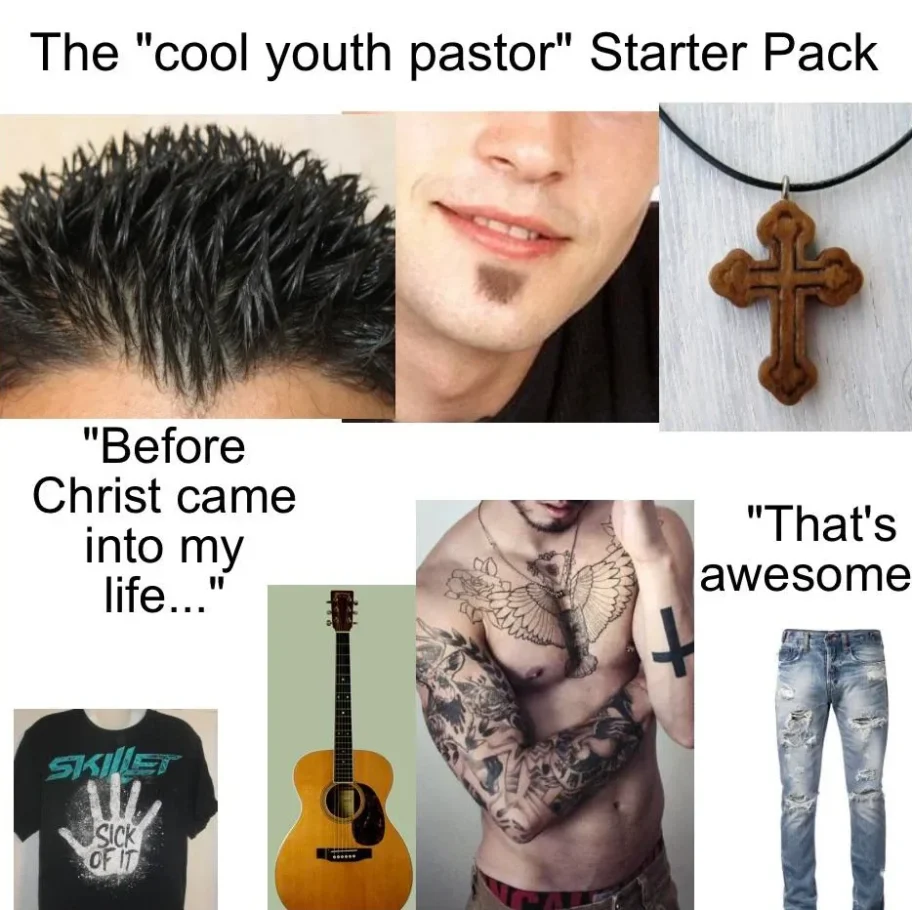

With no official qualifications or rules around who should be hired, evangelical youth pastors usually have less experience than a lead pastor, and they are often hired in their twenties, with traits that make them edgy or attractive to a younger crowd (perhaps some kind of facial hair, a Yeti mug, a shining personality).

There’s no data available to suggest that evangelical youth pastors are arrested for abuse more than other religious leaders, according to Boz Tchividjian, an attorney and a longtime advocate for sex-abuse survivors in religious institutions. But without much supervision and with close proximity to youth, evangelical churches can unwittingly put kids at risk.

“I’m sure a lot of them are repressed,” Tchividjian said of these youth pastors. “They know the words and the theology and the lingo and the culture, and to me, the most dangerous offenders are the people who understand church culture, because they can deceive the easiest.”

The stereotype is that youth pastors (usually young men) are cool and can act like they’re “one of the guys,” a strange mix of being able to influence a teenager while being his or her bud. Some youth pastors are recent seminary graduates, and youth leadership is a necessary step on the church ladder to eventually becoming a head pastor.

“Oftentimes, they’re really charismatic, and the church is thrilled with them,” Tchividjian said. “Parents love that their child is ‘connecting’ with their youth pastor. Then people refuse to believe something could happen.”

However, I do see an upside. Whether through youth groups or other gatherings, the combination of community and religious practice helps root teens in their faith, especially when reminded that they belong to a deeper theological tradition, something that will survive the latest sneaker trend. Teens especially need mentors who walk alongside them, allowing them space to ask questions they don’t always feel they have permission to raise in traditional religious settings.

But I remain conflicted. Raising my own young children in a church now, I am suspicious of youth groups, especially any consumer-based, entertainment-driven ministry; I am also repulsed by fear-based parenting, choices made from a desire to shield children from the evils of this world. But friends with older kids in youth groups tell me that their children have had rich experiences building relationships with Christian peers, and that in a screen-dominated age, it’s better for their teens to be with their peers than scrolling on their phones. Youth pastors can help something old seem new again.