Even in our busy news season, a time of elections and wars, one might have thought that the announcement that a National Book Award will be given next month to a purveyor of antisemitic and homophobic tracts would have caused a bit more of a stir. It seems like the kind of story that would be picked up by major newspapers, public radio, or, at the very least, the trade magazines whose sole purpose is to cover publishing. It is remarkable, then, that there has not been greater attention to the work of William Paul Coates, who will receive the award on Nov. 20. As the publisher of The Jewish Onslaught, as well as assorted other books, Coates has promoted writing that is, in the parlance of our time, problematic, promoting pseudoscience while demeaning Jews and gays, among others.

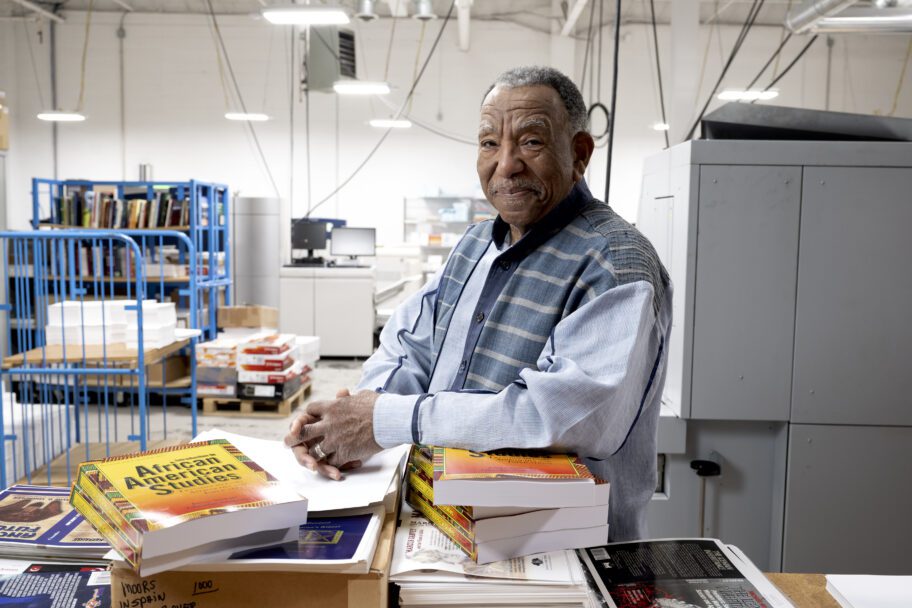

Here’s the story. On Sep. 4, the National Book Foundation, which gives out the National Book Awards, announced that the “literarian” award for outstanding service to the literary community, one of its two lifetime achievement awards, would be awarded to W. Paul Coates, founder of Black Classic Press. “W. Paul Coates has recovered and discovered countless essential works of Black literature, and readers everywhere have reaped the benefits of his passion and care for the written word,” said David Steinberger, chair of the National Book Foundation’s board, in a press release. Ruth Dickey, the foundation’s executive director, added, “As a librarian, publisher, and community activist, W. Paul Coates has been instrumental in preserving the legacy of remarkable writers and elevating works that have shaped our personal and collective understanding of the Black experience within the borders of the United States and around the globe.”

At first glance, Coates was a surprising choice, because from 1997 to 2005 he himself was a member of the National Book Foundation’s Board of Directors. During their deliberations, the members of the program committee, the subset of the board that selects finalists for the lifetime achievement awards, were aware of the conflict. “We had to launder the issue of selecting someone formerly at the table, a board member,” Quang Bao, a member of the program committee, told me. In the end, the committee decided that Coates’s contributions to publishing were so great that he merited selection, notwithstanding their personal connections to him and their affection for him. “One reason I was pressing to get him across the line this year was I miss him,” Bao said.

William Paul Coates was born in 1946 and raised in Philadelphia. Always bookish, while in the Army he encountered Richard Wright’s Black Boy, a transformative experience for him. Later, while working at the Moorland-Spingarn Research Center at Howard University, he conceived Black Classic Press. As his son, Ta-Nehisi Coates, recalls, in his memoir The Beautiful Struggle, “at night,” after coming home from Howard, Paul would “untuck his shirt and descend into the cellar” to be with his collection of “out-of-print texts, obscure lectures, and self-published monographs by writers like J.A. Rogers, Dr. Ben, and Drusilla Dunjee Houston, great seers who returned Egypt to Africa and recorded our history, when all the world said we had none. These were words that they did not want us to see…. But Dad brought them back.”

These texts, many by self-taught scholars, formed the core of what would later be called Afrocentric historiography. Coates believed that the knowledge these writers imparted had been deliberately withheld from Black people. “From the day we touched these stolen shores, [Paul would] explain to anyone who’d listen, they infected our minds,” Ta-Nehisi Coates writes. White people “forged a false Knowledge to keep us down. But against this demonology, there were those who battled back. Universities scorned them. Compromised professors scoffed at their names. So they published themselves and hawked their Knowledge at street fairs, churches, and bazaars. For their efforts, they were forgotten.”

Paul Coates resolved to bring their works back into print, and in 1978 he founded Black Classic Books, “a publishing operation he built from saddle-stitch staplers, a table-top press, and a Commodore 64,” his son would write. Since that time, his company has published books by writers known mainly in Afrocentric circles, as well as books better known, including an edition of David Walker’s Appeal and works by respected figures like W.E.B. Du Bois and the historian Carter G. Woodson. More recently, Black Classic has published books by the best-selling Walter Mosley, giving the press a financial boost.

But on Sep. 27, Jewish Insider published an article by reporter Matthew Kassel, with the headline “Paul Coates, father of journalist Ta-Nehisi Coates, republishing antisemitic screed ‘The Jewish Onslaught.’” “But even as Coates has been celebrated for nurturing such contemporary authors as Walter Mosley and reissuing works by W.E.B. Du Bois, among other luminaries,” Kassel wrote, “his company has also recently chosen to spotlight an antisemitic screed that seeks to uphold a widely discredited conspiracy theory alleging Jewish domination of the Atlantic slave trade.”

Apparently, into Black Classic’s online store, Paul Coates had added The Jewish Onslaught, by the late Wellesley professor Tony Martin (1942-2013). Martin was notorious in the early 1990s for assigning to his students the Nation of Islam text The Secret Relationship Between Blacks and Jews, a widely discredited book that over-stated Jews’ involvement in the slave trade, and made numerous historical errors besides. Martin believed the uproar was fomented by a Jewish cabal including Hillel, B’nai Brith, the Anti-Defamation League, the Jew-controlled media, and their Gentile handmaidens. His response to the criticism of his first book was The Jewish Onslaught: Despatches from the Wellesley Battlefront, which he published in 1993. Martin’s book reiterates and defends the thesis about Jews and slavery, and it connects the dots of a Jewish campaign against him, driven by “the Jewish ability to make a lot of ‘noise’ and fill the media with their lies,” to choose one antisemitic passage among hundreds. Elsewhere, there are passages like, “Jewish lies and distortions were supplemented, perhaps inevitably, by Jewish dirty tricks.”

According to Jewish Insider, Coates refused to answer questions about his inclusion of The Jewish Onslaught on Black Classic’s list (Coates also refused, through an employee at Black Classic, to talk to me). According to a press release on the website, Black Classic was republishing a number of books from Majority Press—the press Tony Martin founded—including works by and about Marcus Garvey. The Jewish Onslaught was one of the Majority Press books that Black Classic was now picking up (this seems to have been in 2022, based on the publication date listed on Amazon). On Black Classic’s page for The Jewish Onslaught, the publicity blurb touted an “essay on Black-Jewish relations, primarily in the United States, by a professor of African American History who became embroiled in controversy over his classroom use of a book detailing the well-documented Jewish role in the Atlantic slave trade.”

On Oct. 11, two weeks after his Jewish Insider article, Kassel reported on X that Black Classic had removed The Jewish Onslaught from its online store.

At this point in the story, one could imagine that this was all something of an accident—that, in acquiring Tony Martin’s back catalogue of books, which are in fact mostly Marcus Garvey–related, Coates thoughtlessly included Martin’s The Jewish Onslaught. Even the fulsome blurb, whitewashing the book’s antisemitism, could have been ported over from an old Majority Press website, perhaps by a clueless intern. At a small press, all hands on deck, mistakes get made.

Except that the closer one looks at Black Classic’s store, the more problematic texts one finds. For example, Black Classic publishes The Osiris Papers: Reflections on the Life and Writings of Dr. Frances Cress Welsing, edited by Raymond Winbush and Denise Wright, a collection of essays celebrating the late psychiatrist Frances Cress Welsing, who around 1970 began advancing the theory that racism in white people is correlated to the lack of melanin in their skin—a theory whose absurdity, describing white people as descended from the “albino mutant offspring” of Black people, did not keep it from spreading widely. For example, in The Beautiful Struggle, Ta-Nehisi Coates writes, of his adolescent self, that he “flirted with the supremacy of melanin”—although he later realized that he had “embraced the charlatans and their stupid science.”

The closer one looks at Black Classic’s store, the more problematic texts one finds.

For good measure, Welsing also believed that homosexuality was imposed by white people on Black men. Black homosexuality might be “reaching epidemic proportions amongst Black people in the U.S.,” she wrote in 1974, “although it was an almost nonexistent behavioral phenomenon amongst indigenous Blacks in Africa.” She ridicules Black men wearing “earrings and bracelets … midriff tops … cinch waisted pants.” A year after the American Psychiatric Association had taken homosexuality off its list of mental disorders, Welsing criticized the decision, which “has nothing to do with the mental health of Black people.”

In the only essay in The Osiris Papers to deal with Welsing’s views on homosexuality, psychologist Denise Wright writes that she will not take sides: “[I]t is not this writer’s intention … to take an antagonist or protagonist position about homosexuality.” The essay is supportive of Welsing, without in any way challenging her view that, as Wright summarizes it, oppression has “caused the Black man to modify the expression of his sexuality/masculinity in more passive ways, which may present as effeminization, and/or engaging in bisexual and homosexual acts.” The Black Classic web page promoting this book calls Welsing “one of the greatest African thinkers of the past 100 years”; one can also find Paul Coates expounding Welsing’s greatness in a video on the press’s website.

For good measure, Welsing also believed that homosexuality was imposed by white people on Black men. The Black Classic web page calls Welsing “one of the greatest African thinkers of the past 100 years.”

Black Classic also offers numerous books by the late Hunter College historian John Henrik Clarke (1915-1998), who shared Welsing’s homophobia. Clarke’s detractors often mention his antisemitism, but his homophobia is sometimes overlooked. On YouTube, you can see him cheered on as he tells an audience that Africans “had a healthy attitude toward things other people made unhealthy and made filthy and dirty.” Scornfully, he denies the possibility of gay Africans in antiquity. “Show me one case of sexual deviation before the coming of foreigners! And yet you’ve got people already on programs [saying] the Africans and the Greeks were both homosexuals…. Now we ain’t had no confusion—we’ve been confused on many things, but not that. We know the difference between mothers and fathers, and what each one’s supposed to do.”

Elsewhere, Clarke opined about the “Jewish educational mafia.” He wrote an introduction to an edition of Michael Bradley’s 1978 book The Iceman Inheritance, which argues that white people are genetically predisposed to higher levels of racism and aggression than other groups; he also wrote the foreword to Bradley’s 1992 work Chosen People from the Caucasus: Jewish Origins, Delusions, Deceptions and Historical Role in the Slave Trade, Genocide and Cultural Colonization. This last work argues that the people known as Jews today are descended from eighth-century converts to Judaism, having usurped the tradition from a group that had been practicing Judaism for more than two millennia; these late-arriving Jews, including today’s Ashkenazi Jews, have uniquely high levels of Neanderthal aggression, which has helped them dominate other groups.

In 2001, Clarke told an interviewer that “the European uses this religion”—Judaism—“as the handmaiden of his imperial desires. I strictly mean the Europeans who answer to the word Jew. He reads the word Jew into ancient history, where the word didn’t exist. When the European Jew didn’t exist.” In an interview you can find online, Clarke told an audience, “If Jews want to dominate something, it’s very easy to dominate us. So that’s what they do. “

The idea that “white” Jews, whether Ashkenazi, Sephardi (Iberian), or Mizrahi (Middle Eastern and North African), are somehow impostors or usurpers—with the “real” Jews coming from the Nile River Valley or other parts of Africa—is a poisonous myth: it plays into stereotypes of Jews as shifty and duplicitous, and it is deployed to subvert Jewish claims to have roots in the land of Israel. But it’s taken as a given within a certain strain of Afrocentric thought, one embraced not only by Clarke but also by the aforementioned “Dr. Ben”—Yosef A.A. ben-Jochannan—who like Clarke was a prolific autodidact who believed that white people had deliberately obscured the history of African greatness, and who like Clarke is well represented in the offerings of Black Classic Press. Black Classic publishes twelve Ben-Jochannan titles, including We the Black Jews: Witness to the “White Jewish Race” Myth and African Origins of the Major Western Religions.

Also like Clarke, ben-Jochannan seems not to have had much higher education—but unlike Clarke, he lied about it. In 2015, shortly after ben-Jochannan’s death at ninety-six, The New York Times reported that for decades he had deceived employers about his credentials, telling Cornell and other institutions that he had degrees from Cambridge, in England, and the University of Puerto Rico Mayagüez. Neither school had a record of his enrollment. “‘People condemn me for not being an intellectual of the Ph.D. type,’ Mr. Ben-Jochannan once said, reacting to questions later raised about his résumé,” the Times wrote. “While he used the ‘white man’s credential’ to go ‘certain places,’ Mr. Ben-Jochannan said, he refused to ‘let the white man certify’ his work.”

In 2001, Clarke told an interviewer that “the European uses this religion”—Judaism—“as the handmaiden of his imperial desires. I strictly mean the Europeans who answer to the word Jew. He reads the word Jew into ancient history, where the word didn’t exist. When the European Jew didn’t exist.”

As far as I can tell, Paul Coates has nowhere discussed the allegations against ben-Jochannan, his longtime intellectual partner—and a writer who remains a source of revenue for the press. To the contrary, Coates has always spoken of ben-Jochannan with reverence. “In 1978, when we started publishing, three elders were inspirations and gave their support—John G. Jackson, John Henrik Clarke and Yosef ben-Jochannan,” writes Coates on the Black Classic website. “His books have revolutionized the way Black people relate to Africa and the Nile Valley.” After ben-Jochannan’s death, Coates told the Times, “I consider Dr. Ben the greatest of the self-trained historians.” Ta-Nehisi Coates told the Times that ben-Jochannan’s example “runs through everything I do.”

Along with Clarke and ben-Jochannan, one of the authors best represented in Black Classic’s offerings remains Tony Martin—The Jewish Onslaught may be gone from the website, but several of his other books are still there. One of them is a short pamphlet, published in 1998, containing the text of a lecture given in 1997 in Trinidad. It’s available for five dollars plus shipping. Titled The Progress of the African Race Since Emancipation and Prospects for the Future, it is largely about the Afro-Caribbean experience, but in several places it mentions Jews.

On page four, for example, one finds Martin recycling the antisemitic canard that racism was invented by the Jews: “Pseudo-scientific racism had been around since at least the 4th or 5th century AD when the Jewish holy book, the Talmud, pioneered the notion that Africans were recipients of the curse of Ham.” But the Talmud makes no connection between Noah’s son Ham and Africa; that is a later, mainly Christian tradition, seen in early church theologians like Eusebius of Caesarea (ca. 260-340) and Bede (673-735). This bit of anti-Talmud invective is simply an urban legend, popular among antisemites, not limited to Afrocentrists.

Later in the pamphlet, discussing the extent of worldwide Jewish power—which he grudgingly admires, and believes Africans should emulate—Martin writes, “When President Clinton becomes president, he goes to Geneva and he bows down before the World Jewish Congress. When the African American woman Myrlie Evers Williams became head of the NAACP the other day, she went straight to Geneva and bowed down before the World Jewish Congress.” This is fiction. President Clinton traveled to Geneva four times during his presidency, but never to meet with the World Jewish Congress. There is no evidence that Evers Williams ever met with the Jewish group in Geneva, although she once addressed the group when it met in New York, which is its actual headquarters (not Geneva). In short, the impression Martin gives, that world leaders travel thousands of miles to pledge fealty to a high council of Jews, is false in every regard.

None of this should be surprising coming from Martin, who elsewhere in his pamphlet calls the World Jewish Congress “a body organized on a racial or religious or whatever-the-Jews-are basis.” One has to ask: Why is Paul Coates selling this?

At the time that Coates founded Black Classic Press, Anglophone universities were beginning to open departments of African American studies (then often called Afro-American studies, or sometimes Africana studies). Between 1968 and 1970, departments (or “programs,” which often did not have the funding or hiring power of full departments) opened at San Francisco State, Cornell, Yale, Harvard, Berkeley, and Michigan. As these schools, and soon dozens more, began to offer classes that focused on the Black (then “black”) experience, they needed faculty. More graduate students began to write dissertations on African, African American, and Black Caribbean experiences. This was also about the time that scholars like David Brion Davis, Eugene Genovese, Sterling Stuckey, and Albert J. Raboteau put the field of slavery studies on the map.

For some, especially in universities, the old classics (by Du Bois, Woodson, John Hope Franklin, Benjamin Quarles, etc.) and the exciting new work (by the aforementioned scholars and others, soon to include women like Nell Irvin Painter, and Barbara J. Fields, among many others), were enough to fill their bookshelves. But parallel to this academic literature, there was an emerging literature for those outside the academy. Even with the explosion of scholarship about the Civil War, slavery, Reconstruction, the Harlem Renaissance, and Black participation in every epoch of history, from the ancient world (Howard University classicist Frank M. Snowden Jr. published his pioneering Blacks in Antiquity: Ethiopians in the Greco-Roman Experience in 1970) to the present, there was still a sense among radicals and Afrocentrists that real truths were going untold, or were being deliberately obscured.

Just as political radicals mistrusted mainstream liberals, academic radicals took a dim view of mainstream scholarship; they began constructing a canon of Afrocentric scholarship. The historian Mia Bay has called Afrocentrism “[e]ssentially an approach to Black Studies and black life … first and foremost a product of the Black Power culture of the 1970s.” She is referring to the theories of Molefi Kete Asante specifically, but she argues that his school of thought encompassed works by Welsing, Black Press author Wade W. Nobles (another “melanist”), and others. Bibliophiles and archivists like Coates—himself a veteran Black Power activist—were discovering an older canon of radical, outsider, Afrocentrist writing, principally by self-taught, non-credentialed amateurs, like Drusilla Dunjee Houston (who published Wonderful Ethiopians of the Ancient Cushite Empire in 1926; she was trained as a pianist, not a historian), and educated Africans and West Indians who remained obscure in the United States, like Edward B. Blyden, whose 1888 work Christianity, Islam and the Negro Race made an early case for Islam as a more natural religion for Black people than Christianity.

Sometimes the Afrocentric autodidacts ended up with university positions, either without advanced degrees (like Clarke, until his retirement) or by lying about advanced degrees (like ben-Jochannan). Some of this new Afrocentrism trafficked in conspiracy theories or, like Welsing’s melanin theory, abject pseudo-science. At the same time, some of the work was useful. And some of it was not particularly radical, just forgotten, ready to be reclaimed by new generations. New enterprises were needed, and the late 1960s and 1970s were a time of new enterprises, like women’s bookstores, gay bookstores, and Black bookstores. Small, radical publishers, too. Third World Press, which claims to be the oldest Black publishing company in the world, and which also has published Welsing, Clarke, and other Black Classic authors, was founded in 1967, eleven years before Coates founded Black Classic.

Before he settled into publishing, Coates’s grand ambition, as described in his son’s memoir, was a “new revolution” comprising “three parts—a bookstore, a printer, and a publisher—that would give the people control of information.” It would be, Ta-Nehisi Coates writes, “a propaganda machine.” The goal was propaganda. And it may be the case that, if your mission is Afrocentric propaganda, you might overlook the antisemitism of the authors you publish (the homophobia, too), for a host of reasons that have nothing to do with animus against Jews: Because your authors are “conscious,” and useful to the cause. Or because you think they will lift Black people up, and you’re not too worried if, in their small way, they push Jews down, peddling lies about a too-powerful people, religion, race, or, to quote Tony Martin, “whatever-the-Jews-are.”

Or because, having once published or sold someone like Tony Martin, you are loathe to abandon him. As the historian Robin D.G. Kelley wrote, in an essay about John Henrik Clarke, “As professor of black and Puerto Rican studies at Hunter College in New York and a founder of black studies, Clarke defended his colleague Leonard Jeffries, even though he thought the theory Jeffries promulgated—that Africans are ‘sun people’ and Europeans ‘ice people’ … smacked of racial determinism. But Clarke was an old-school race man who recoiled when white folks tried to regulate black people’s associations and alliances.” I imagine Coates would recoil, too. As would I.

To be sure, anything significant should be published. Harper currently sells an edition of Hitler’s Mein Kampf, with an introduction that puts it in context. There are repellent people who are interesting writers, whose works should be in print. I am thinking of someone like the late rabbi Meir Kahane, a violent racist who nevertheless wrote books that serious students of modern Jewish history should read, because they have been influential. By the same logic, we ought to keep watching the racist movies of D.W. Griffith and Leni Riefenstahl. Somebody has to keep these books in print, and to keep these movies available. But a responsible publisher puts the work in context, whether through critical introductions in the books themselves, collateral educational material, or thoughtful blurbs in the catalogue or on the website; there are numerous ways to position offensive, problematic, but historically significant works as subjects of discussion.

But Coates’s marketing of racist, antisemitic, and homophobic books and authors is enthusiastic and uncritical. It reminds me of a man I once interviewed, Mark Weber, leader of the Institute for Historical Review. Weber publishes works of antisemitism, racism, and Holocaust revisionism; he publishes these books not as subjects of critical study, or as historical artifacts, but as useful tools of his ideological project. Browse his online store, and you will see that Weber sells books by Holocaust denier David Irving, CDs of pro-fascist speeches by Charles Lindbergh, and—as it happens—a speech by Black Classic author Tony Martin. The IHR sells Martin’s Tactics of Organized Jewry in Suppressing Free Speech (the CD is $9.95, the DVD is $15.95). So if you want the antisemitic conspiracy theories of Tony Martin, you can get them from a Holocaust-denial website or from Black Classic Press.

As to why the National Book Foundation is choosing to honor Paul Coates, that is a more interesting question. Anyone who can sustain an independent press for nearly half a century is a force of nature. In a perceptive 2017 article, Yale scholar Roderick Ferguson makes the case for Coates, who has also edited a collection on Black book collectors, as one of the Black “bibliomaniacs,” working outside the academy, who “through the texts that they collected on the African roots of Western civilization and the histories of black radicalism in North America, Europe, Africa, and the Caribbean” helped shape the emerging discipline of Black studies. These bibliomaniacs were sometimes librarians, sometimes archivists or curators, sometimes street vendors hawking books on sidewalk tables—at times, Paul Coates was all of the above.

“Coates’s history and that of black bibliophiles, in general, strikes at the heart of an ideological contention within black studies,” Ferguson writes. “This contention has to do with the question of who has the right to articulate knowledge within black studies. This ideological debate is founded on the division between the scholar with university certification and methodological training versus the uncertified autodidact who learns by serendipity…. Coates represents the self-trained organic intellectual who—by circumstance or intention—bypasses the approved methods of scholarly development and certification.”

The debate was between those with credentials and those without them. But it can be simplified further: it is a contest between those who prioritize conventional scholarly practices in their attempt to get facts right, and those who don’t, or can’t. As the Cornell scholar Martin Bernal—himself something of an Afrocentrist, author of the two-volume Black Athena: The Afroasiatic Roots of Classical Culture—wrote in 1996, “That Afrocentrists should make so many mistakes is understandable. Theirs is a sense of being embattled in a hostile world and of possessing an absolute truth that makes for less concern about factual detail. More important, however, are the extraordinary material difficulties confronted in acquiring training in the requisite languages, in finding time and space to carry on research, money to buy books or access to libraries, let alone finding publishers who can provide academic checks and competent proofreaders.”

It seems that Coates may be aware that he publishes some pretty implausible stuff. In 2003, at the Harlem Book Fair, Coates noted that ben-Jochannan was in the audience, and he said, “It was Dr. Ben who repeated the words to me that gave me really the crux of our publishing, that ‘the African’s right to be wrong is sacred.’ That was wonderful ground to stand on for me, because it gave me the understanding that our voice was that important. So even if it was the wrong voice, I had access to it. If it was the right voice, whatever, I had access to it, and I could publish that voice.” Referring to the former New Republic publisher Martin Peretz, who taught at Harvard, Ta-Nehisi Coates quoted the same line. “My pops said this shit to me one time: ‘The African’s right to be wrong is sacred.’ When we’re wrong, it’s craziness, but when they’re wrong, it’s … Harvard.”

“Coates’s history and that of black bibliophiles, in general, strikes at the heart of an ideological contention within black studies,” Ferguson writes. “This contention has to do with the question of who has the right to articulate knowledge within black studies.”

Be that as it may, it is pure condescension not to interrogate the quality of these books, or the reliability of the authors. It is one thing to say that no proper history of Black studies can ignore the role someone like ben-Jochannan played in the discipline (in part as a figure that more respectable scholars ran away from). It’s another thing to work as a propagandist for the man’s legend, while ignoring both the implausibility of his claims and his trumped-up credentials. And it’s a form of racism, however well-intentioned, on the part of the National Book Foundation’s elite, credentialed litterateurs—Black, white, Latino, Asian, etc.—not to worry about this distinction between propaganda and scholarship.

Even if the books’ quality did not disqualify Coates from a National Book Award, one would expect that the antisemitism would. Or the falsified résumé of someone like ben-Jochannan (although, to be fair, there are white fabulists and plagiarists who still have publishers). And if the dissembling and antisemitism weren’t problems for the judges, what about the homophobia?

But what if nobody on the National Book Foundation’s program committee, or on the whole board of directors, read the books? It is difficult to know. Quang Bao said that the other members of the committee in 2024 were Morgan Entrekin, publisher of Grove/Atlantic; Lisa Lucas, until recently head of Random House’s Pantheon and Schocken divisions; Calvin Sims, an executive at CNN; and the novelist and screenwriter Charles Yu. I tried to reach all four of them, by email, telephone, or both. None got back to me. Nor did board chair David Steinberger, board vice chair Fiona McCrae, board treasurer Elpidio Villareal, or board member Kenneth L. Wallach. Ruth Dickey, the Foundation’s executive director, did not return multiple calls and emails. Here is what Bao told me about the selection process:

Paul has been up for it every year. We have a long list, a short list—it’s a matter of, “Why this person now?” I can answer that best by saying we are in a heightened consciousness about African American literature, the African American experience…. He is a publisher, but not in New York City. He is a Black publisher focused on historical Black works, not a white editor. And he was a librarian for so long in his life, which meant to me his contemporary effort has a historical, diasporic reach. That is the deeper activism going on here.

When asked if he had read any of Coates’s books, Bao said that he had been assigned, in a graduate class he is taking, an excerpt by Walter Mosley. But he was unfamiliar with the bread and butter of what Black Classic Press publishes.

After the program committee chooses “two or three” finalists for each award, Bao said, it forwards its recommendations, along with biographies of the candidates, to the whole board of directors. That means the final decision to give Coates the award would have rested with all the board members, including Anthony W. Marx, president of the New York Public Library, and Julia A. Reidhead, president of the publisher W.W. Norton, neither of whom would speak with me.

That Coates is getting his award in part, as Bao sees it, to honor his “deeper activism,” his “diasporic reach,” and his status as a Black editor from the provinces, i.e., not New York City—none of this is surprising, or even alarming. And if it helped Coates that he has a famous son, that too would be par for the course. The book industry has long been filled with nepotism, virtue signaling, and sloppy reading by people paid to read. What seems unusual, in this case, is not the virtue signaling but rather its selective application. To atone for past sins against Black people, the industry is overlooking offenses against Jewish and queer people.

The problem is not Paul Coates, not really. He could run a better press, to be sure, with higher editorial standards—but he is a recognizable American type, or rather congeries of types: collector, ideological obsessive, pamphleteer, archivist, evangelist, hawker of wares. Bring these traits together, you often end up with someone in self-publishing, or small-press publishing. Every ethnic or religious community—every community—has this guy, selling the books and pamphlets that more mainstream outlets ignore. Some of those books and pamphlets will be interesting, even valuable, and some will say crazy things, which, most of the time, can be safely ignored.

But at a time when truth is under attack as seldom before in American history, it won’t do to be casual or glib about it. We can’t lie to ourselves, or pretend that history is only a power game. None of us need care about who gets literary awards, but we should care about calling out bigotry, deception, and bad scholarship. If Coates has a defense of his authors’ views of Jews and gay men, he should come out with it. If he thinks “melanists” are onto something, he should say so. If he believes that peddling Tony Martin’s antisemitic lies is a responsible thing to do, he should say why. And if the directors of the National Book Foundation believe that these are unreasonable questions, that there’s nothing to see here, they should explain their thinking. But first, they should do the reading.