On October 24, after a seven-year dispute that—depending on whom you ask—was either about traffic or Islamophobia in the majority-Christian town of Oyster Bay, N.Y., local officials finally agreed to allow a mosque to expand. And while this battle, played out in the suburbs of Long Island, is now resolved, some see it as typical of anti-Muslim sentiment in our anti-immigrant age.

“There are now people who have written textbooks on how to oppose mosques,” said a person familiar with the case, who asked not to be identified due to conditions of the settlement. “They teach municipalities to talk about parking issues and traffic. The opposition [to mosques] has grown in sophistication ten-fold since they realized they don’t get anywhere using anti-immigrant and anti-Islamic speech.”

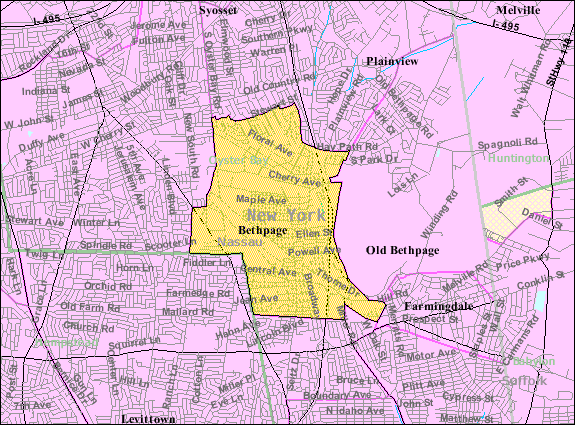

Masjid al-Baqi, the mosque at the center of the Long Island dispute, and the town of Oyster Bay, thirty-eight miles east of Manhattan, reached an agreement two days before they were set to face each other in court. The case centered around the expansion of the mosque, which opened in a converted fast food restaurant in the Bethpage section of town in 1998.

According to Oyster Bay’s local newspaper, the mosque currently gets about two hundred worshippers at Friday prayers, most of them of Afghan, Bangladeshi, Indian, or Pakistani backgrounds. Bethpage has about 17,000 residents and is largely white. Muslims on Long Island Inc., which owns the mosque, agreed to reduce the expansion’s size, while the town dropped a law that would have required more parking spaces.

“These are people who have invested their lives and money in the local community and they want equal treatment under the law,” the person familiar with the case said. “This is about standing up and letting everyone in the community know that Muslim Americans have equal rights.”

The Bethpage mosque drama is one of many instances of community-based opposition to Muslim-sponsored building projects. Currently, the most high-profile example is EPIC City, an Islamic community near Dallas proposed by the East Plano Islamic Center. Although mosque officials have repeatedly stated the planned four-hundred-acre town with a mosque at its center would be open to all, Texas governor Greg Abbott wants it banned. “Sharia law is not allowed in Texas,” he said on X last February.

Oyster Bay has a history of throwing roadblocks in the paths of non-Christian worshippers. It delayed the revamping of a Sikh temple for five years, and nearby Hempstead tried to halt the expansion of an Islamic center. These local conflicts played out against the memory of the battle over the so-called “Ground Zero mosque” in downtown Manhattan, in the wake of the 2001 terrorist attacks. According to the American Civil Liberties Union, New York state has seen thirty-five incidents of anti-mosque activitiy since 2010, among the highest in the nation. Five of these involved the erection of or expansion of mosques.

Mitra Rastegar, who teaches at New York University and studies Muslims in America, said mosques are the most commonly protested houses of worship. “My perception is that these challenges have increased since about 2010,” she said, “but we might also note that the number of mosques in the U.S. has also increased in that time period.”

“These are people who have invested their lives and money in the local community and they want equal treatment under the law.”

Meanwhile, Islamophobia is on the rise. The Institute for Social Policy and Understanding says its National American Islamophobia Index, a means for measuring the prevalence and resonance of negative Islamic stereotypes, shows an eight-point jump since 2022.

Evidence of such Islamophobia was on display in Oyster Bay when Masjid al-Baqi’s expansion on its existing site was proposed in 2018. Muslims on Long Island Inc. sought to tear down the existing building and erect a three-story building, with a washing station (required before Islamic prayers), as well as a place for holy day meals and for children’s activities. The plan cleared most of the usual hurdles—environmental impact report, plumbing compliance, etc.—and, by 2022, it seemed that construction would begin.

Then town officials grew cold. They raised concerns about a high number of red-light violations at the mosque’s intersection. Then they passed a parking ordinance that required the mosque to include 155 parking spaces—more than town law requires for either theaters or libraries. The mosque had room for only 86, which was sufficient before the new ordinance.

In January 2024, non-Muslim residents at a public meeting expressed reservations that had nothing to do with traffic or parking spaces.

“I don’t want to sound racist or anything,” one resident, Diane Storey, said at the time. “But there’s been a big influx of, I don’t want to call them Indian, but I don’t know where they’re from.” Another said they did not like the fact that Muslim men and women pray and worship separately, and another claimed Muslims did not add to the community as church-goers do.

A “Stop the Mosque” petition circulated online. To date it has just over two thousand signatures and a comments section peppered with anti-Muslim feeling. One signatory commented, “Given the violence against Christians by a few and the intolerance being displayed today by many I don’t want these zealots in our country.”

Last January, mosque leaders sued the town of Oyster Bay, saying their religious freedom was being violated under the Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Persons Act (RLUIPA). That 2000 law prohibits religious discrimination in zoning. In depositions, two planning board officials admitted the remarks of a grandmother concerned about increased traffic, a figure cited in rejecting the expansion, was “a composite character that didn’t exist.”

In July, the federal government sided with Muslims on Long Island Inc., and in August, Oyster Bay settled with them for almost $4 million, intended to cover the mosque’s legal fees. But town officials did not approve the deal, and by September the parties were back in court.

Now, under the settlement, the town has repealed its parking ordinance. Muslims on Long Island Inc. originally sought to build a 16,000-square-foot, multi-story building, but has shaved the size to less than 10,000 square-feet. They also agreed to pay for a traffic officer at their intersection for eighteen months.

Mosque leaders have maintained silence since the settlement. In September, Mujahid Ahmed, a worshipper at the mosque and a local resident for twenty-five years, told The New York Times, “We are members of this town. We are as Bethpagean as it gets.”